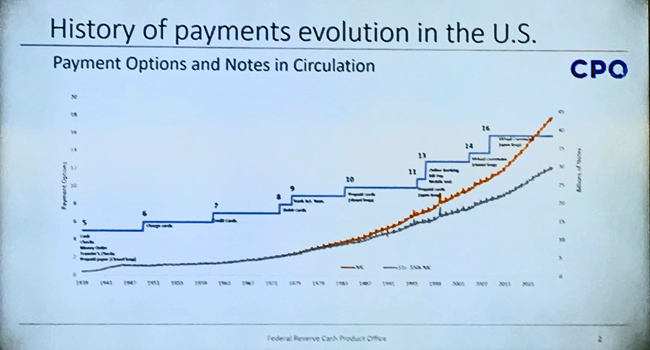

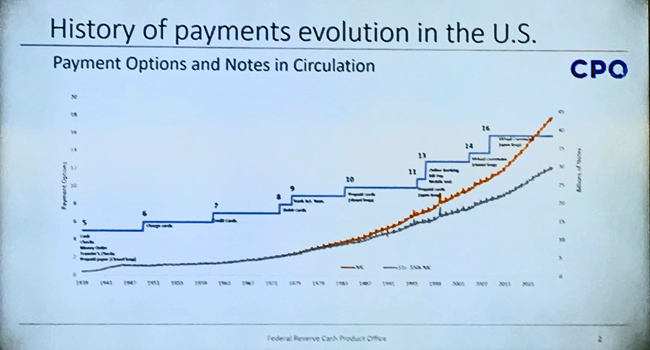

Moving money faster remains a persistent challenge in the United States. Consumers continue their wary adoption of mobile payments; cards remain the primary payment method of choice at the point of sale, and cash in circulation continues to grow faster than U.S. gross domestic product. Corporations, for their part, still prefer checks.

The situation is changing, and it’s a good time to be in payments, according to many attendees at last week’s Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago Payments Symposium. U.S. consumers and businesses have greater payments choice than ever, from realtime systems to cash.

Financial technology firms can adapt the current payments infrastructure to handle new situations and are envisioning an even more interconnected payments future. Yet payments innovation is still a long haul in the United States.

Source: Photo of a slide from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Cash Product Office (CPO). The top orange line is cash in circulation; the bottom is cash used in commerce.

“There is overwhelming enthusiasm by the banks for realtime corporate payments,” said Grace Klopcic, partner, McKinsey & Company. “We have not seen an uptick beyond person-to-person (P2P) payments. It will take some time to see what the impact will be on B2B.”

Even so, she said, payments revenue globally is on the rise. After 11% growth in 2017, payments revenue grew at its usual 6% rate in 2018. “A lot of the global growth in payments is in the context of faster payments,” she said.

Open APIs

The technical interconnections between banks, payments providers, corporate treasury systems, and retail consumers will be open APIs. Application programming interfaces using open-source REST protocols have become the API connection of choice software developers today.

“Open APIs. That’s where we’re headed,” said Mike Bilsky head of U.S. Faster Payments Council and CEO, North American Banking Company. The move for banks to provide open API connections began with the regulatory changes mandated in the European Union under the Payment Service Directive 2 (PSD2) rules, which emphasize consumer choice in payments providers and consumer ownership of data.

Although the United States is unlikely to adopt similar regulations, open APIs enable systems designs in which payments are embedded and take place in the background. They also provide opportunities to create services for clients that never existed before, “where companies that are not in payments who need to move money can connect with banks who can,” said Ben Milne, founder of payments technology developer Dwolla.

Cross-border payments, the long-time payments problem child, are making progress as well. New service introductions by long-time providers and new technologies developed by new firms have eased some of the long-standing pain points of sending the receiving payments internationally. “I would argue that domestic payments are worse now,” remarked Erin McCune, a partner at payments consultancy Glenbrook Partners. “There’s an awful lot of paper.”

Corporate treasurers sometimes have to move money weeks in advance, foregoing investment gains, to provide liquidity for payments, noted David Tao, treasurer at Gusto. Realtime payments will help. “That kind of just-in-time funding frees up a lot of capital,” he said.

At the same time, corporate finance professionals tend to be more resistant to change than the bankers offering products. Budgets for internal technology, as opposed to customer-facing systems, tend to be leaner. The journey toward faster payments on the business side likely will be longer.

FinTech Workarounds

The payments apps and services provided by FinTech firms substantially amount to “workarounds for the failure of the banking industry to provide a realtime payments infrastructure,” said Carol Coye Benson, partner at Glenbrook Partners. “It begs the question that, after finally getting our act together to do realtime payments in depository banks, what happens to those services?”

The FinTechs that are not workarounds are generally doing things around alternative business models or improving operations to reduce the costs. As for blockchain technology and nongovernmental currencies bitcoin and Facebook’s Libra, Coye Benson said:

“I would just ask you not to be blinded by the myriad failures with the current set and not lose track of the opportunity as these products evolve. If they can prove safe, fast, cheap ways of storing money and moving money, they will succeed eventually over time.”

Matthias Schmudde, head of payments and securities clearance at Deutsche Bundesbank, had a similar observation, relating to bank perspectives on regulation. Regulatory actions are correcting points where the banking industry failed to do its job. “That’s the approach many banks are starting follow,” he said.

Not, for the most part, in the United States, said Laurence Cooke, founder and CEO, at treasury technology developer NanoPay. “London has been the payments innovator. The U.S. is massively behind on payments. Now it’s telecom, where China is ahead. The U.S. used to lead innovation all over.”

Technologists argued that the recently announced FedNow faster payments system will not close the gap, citing both the initial enthusiasm and regulatory response to Libra as evidence. Despite its design flaws, Libra surfaced the pain points in the current system that faster payments will not solve.

In making his case for a complete redesign of the underlying payments infrastructure and technology, Steve Kirsch, CEO at open API banking developer Token, argued, “It’s not like the iPhone came out with a bunch of apps. It was an enabler. Just like the internet. FTP (file transfer protocol) and email were all people imagined. The business processes were unlocked by the platform.”